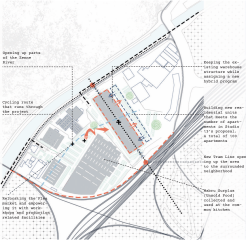

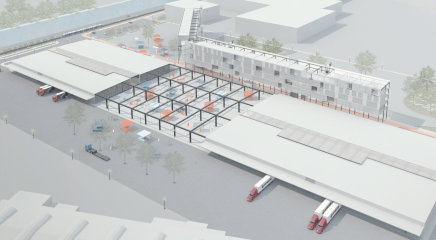

Having said that, I will base my research on two main questions: What are the alternative approaches to the urban transformation in Mabru to address and challenge the existing social and spatial inequalities? How can the loose space be rethought as an urban commons to alter the existing modes of social, spatial, and productive interactions? Envisioning a post-industrial city beyond a place of consumption and inequality. Rethinking the existing Base-Superstructure to challenge the existing power structures to stop reproducing the existing inequalities in our cities.

Over the past decades, the renewal of the European cities along with the rapid growth of services, globalized free market, high tech industries, and knowledge-based economics have driven the industry outside the city. Turning the city into a place of consumption instead of production.

Since the city itself and its citizens resist the recurrent neoliberal system in diverse ways. They express their dissatisfaction through transgressive acts that range From obvious forms of mass protests (ex. Protests in Lebanon, Chile, Ecuador, or boycotts) to more subtle forms (ex. Graffiti, dance, or art). Likewise, one form of resisting the dominant social order of global capitalism is organizing a common life by people themselves. (Stavrides, 2016)

Thus, the commons is, “a social system that refers to resources managed and shared according to the rules and the norms defined by the productive community.” (As defined by Kostakis & Drechsler, 2018). As such, the commons architecture can be used as a tool to reinvent shared spaces and inhabit diverse practices based on cooperation and solidarity. Accordingly, envisioning loose spaces at Brussels Flea Market space as a common resource that supports and gives space to diverse kinds of economies, jobs, and social activities.

References

Franck, K., & Stevens, Quentin. (2006). Loose space: Possibility and diversity in urban life. London: Routledge.

Harvey, D. (2012). Rebel cities: From the right to the city to the urban revolution. London: Verso.

Stavrides, S. (2016). Common space: The city as commons (In com- mon). London: Zed Books.